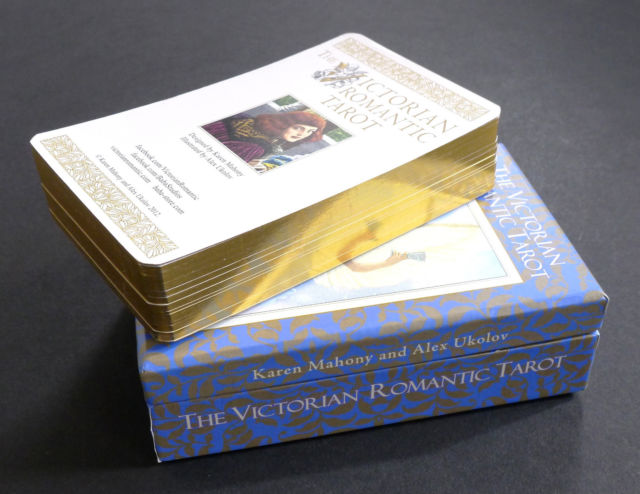

History of Tarot

The Tarot is a pack of mysterious cards which are related to our ordinary modern playing cards and are often said to be their ancestors. Card games were played with them and still are, here and there in Europe, but they are now far more widely used in fortune-telling and for mystical and magical purposes. All sorts of theories and legends have gathered round the cards, because of their puzzling but enticing symbolism and the uncertainty of their origin. It has been said that they came from China or India or Persia, that they were brought to the West by the gypsies, or by returning Crusaders, or by the Arab invaders of Sicily or Spain, or alternatively that they had nothing to do with the East at all and were invented in Europe.

It has been claimed that the Tarot preserves the wisdom of ancient Egypt, the mystery religion of Mithras, pagan Celtic traditions, the beliefs of medieval heretics, or the teachings of a committee of learned Cabalists who supposedly designed the pack in Morocco in the year 1200. Or again, the imagery of the Tarot has been traced to the collective unconscious, or to the symbolism of Dante’s Divine Comedy.  The name Tarot itself has been derived from Egyptian, Hebrew or Latin, and by one ingenious writer from Astaroth, the fertility goddess of Syria and Palestine, condemned in the Old Testament for the sensuality of her rites. The most startling theory is that Tarot comes from the Goddess Tara (another form of Kali as worshipped in Bengal) and links the 22 major arcane cards to her 22 aspects.

The name Tarot itself has been derived from Egyptian, Hebrew or Latin, and by one ingenious writer from Astaroth, the fertility goddess of Syria and Palestine, condemned in the Old Testament for the sensuality of her rites. The most startling theory is that Tarot comes from the Goddess Tara (another form of Kali as worshipped in Bengal) and links the 22 major arcane cards to her 22 aspects.

What stands our among the welter of conflicting theories is that the Tarot cards have something peculiarly fascinating about them. Most of the modern packs are painfully ugly, but some of the older cards are very beautiful and have an air of profound significance. They tug at half-buried memories and obscure connections and intimations in the mind, at associations with mythology, legend, magic and folk belief. They give an impression of holding the key to some vital secret which cannot quite be put into words, which is almost in the mind’s grasp when it slips elusively away. It is because they do this that so many different meanings have been read into them.